After not posting on here for over a year, I am back! This is an older post that I just finished up, but within the next couple weeks I hope to post something new related to my amazing experience studying abroad in Ecuador. For now, please enjoy the following thoughts on different chains of food production/processing/distribution:

The ways food gets to us today are extremely different from the ways it did 100 years ago. We all have a general idea that the way food is grown and distributed has modernized in many ways; many farmers now manage pests and soil health with complex chemical products derived from bacteria or petroleum or other substances, and apply these products with intricate machinery, etc. I often tend to think of how on-farm practices have changed rather than considering the actual structural changes in the chain of producers and processors that bring food to our plate. This latter topic often goes unconsidered. I think it is interesting and insightful to examine the modern food system with a perspective focused on the actual structure of the food chain (i.e. the relationships between different players in the food chain). This perspective also helps to understand the origin of the modern local food movement.

Knowing this, I decided to write a paper for my geography class on the modernization of the food chain (rather than of on-farm practices) and the development of alternative food chains (i.e. the food chains which produce “local” food). As it was a geography class and not an environmental studies class, I chose to focus on the effects these different food chains have on rural communities rather than the environment. While this is a different subject matter and approach than my usual one, I still think it is an important and fascinating topic. And much of the paper examines more general and widely applicable trends in agriculture which I think are important to be aware of as a consumer.

The paper begins with an extremely simplified history of the modernization of the food chain and producers’ and consumers’ reactions to this food chain which together helped create alternative food chains. I attempt to explain briefly the major cause of the current economic hardship faced by many farmers, which I feel is something often talked about but not understood on a deeper level. After that I get to the focus of the essay, the effects of all these things on rural communities. If any of this sounds interesting to you, keep reading! Toward the end, I try to provide a somewhat new perspective on the local food movement. If you are interested but not feeling up for reading all of it, I think the first five or six short paragraphs are a good general overview. I also added some pictures in an attempt to break up the text and make it more manageable. (Be prepared for formal academic writing, apologies for that. But the ideas are still pretty cool, I promise.) Here’s the essay:

Activists, young people, and scientists alike are increasingly interested in food and agriculture and studying its environmental and social impacts. However, much of this increased interest has been focused on either on-farm practices or a very simplified view of the entire food production-consumption chain. In an attempt to study the entire food chain more deeply and with a different perspective, I aim to investigate the changes in the structure and relationships of this food chain over time. More importantly, I make it my goal to identify the effects of these food chain changes on rural spaces, communities, and economies.

In my research I have found that the modernization of the food chain has caused farm consolidation and subsequent decreases in rural population. Additionally, this modernization can cause more specific and nuanced economic harm and political divisions among rural communities. Finally, the recent movement against the modernized food chain and towards alternative, relocalized food chains has had positive but complex economic effects on rural communities, increasing farmers’ incomes but also causing more nuanced disturbances in these communities.

In order to understand these wider effects of food chain modernization on rural areas, it is important to have a thorough idea of what this modernization entails. To briefly summarize this very complex process, the food supply chain has become more “industrial, capitalist, concentrated, and globally integrated” over the last hundred years, and especially since the post-World War II period of economic prosperity (Hinrichs, 2003: 34). This means that in addition to the industrialization of on-farm practices which is often spoken about, the chain from food production to consumption has spread out geographically and economically. The scale at which food is distributed has increased greatly from that of the household or locality to that of the region, nation, and globe.

Instead of a family growing, processing, and eating its own food, these processes have been “delink[ed]” so that the food chain from production to consumption now comprises many more “economic components”: separate industries devoted to producing farm inputs and services as well as those engaged in the processing, packaging, transporting, wholesaling, and retailing of farm products (Hinrichs, 2003: 34; Polopolus, 1982: 803). An example of this trend can be seen in a 1922 issue of the Pacific Rural Press newspaper, which reported on a new business developed to bring refrigeration to rail cars: “The Western Pacific Railroad is to have its own refrigerator car service in 1923. A separate company has been formed to handle this business known as the Western Refrigerator Line.” (Pacific Rural Press, 1922). Here we can begin to see the changes in food chain structure that is a large part of its modernization.

Found in this 2011 FDA report, the above picture gives an idea of the different possible “global supply chains” that canned tuna may take to get to a consumer in the U.S. This representation seems to leave out the actual production of the tuna and the sourcing of various materials necessary for its farming or capture in the wild, which would no doubt add many more paths. We certainly do not think about this complex, global chain or the sheer distance traveled when we sit down to eat a can of tuna.

Within this modernized and “highly interdependent subsystem” of food production and distribution, the corporations which make up the non-production components of the food chain (i.e. everyone but the farmer) have slowly increased their economic influence and share of the food chain (Polopolus, 1983: 803). In 1982, these non-farm components (which hardly existed 150 years earlier) were roughly twice as economically important as the farm itself, based on metrics such as employment and value added (Polopolus, 1983: 803). This increasing economic influence of non-production food chain components has resulted in what Cochrane and others term the “cost-price squeeze” for farmers, in which rising input costs and falling food prices during the 1950s and 1960s put economic pressure on the farmer from both sides (Cochrane, 1979: 386).

Increasing output to attempt to survive this squeeze became more difficult toward the end of the 20th century because of market saturation and “growing opposition to the ‘dumping’ of surpluses on world markets” (Banks et al., 2003: 397). Putting all these factors together, the increasing economic influence of the non-production components of the food chain and subsequent cost-price squeeze caused by the modernization of the food chain have made it significantly more difficult for conventional farmers to sustain their livelihoods on farming alone. This economic harm to farmers can be seen quantitatively in the decreasing share of food prices which are actually paid to the farmer. For example, in 1973 farmers received 44 cents of each dollar spent on food, whereas in 2008, they received only 16 cents of each food dollar (Polopolus, 1982: 804; Canning, 2001: 6).

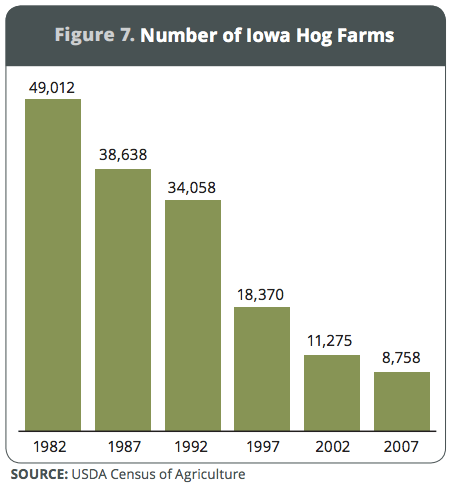

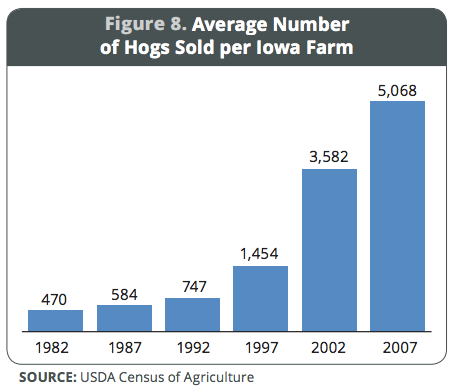

The increasing economic hardship faced by farmers and caused by modernization of the food chain has had varied direct and indirect effects on rural spaces over time. Most simply, this hardship leads to farm consolidation, in which farmers who can not survive the cost-price squeeze are forced to stop farming and move out, selling land to their neighbor who then increases in size and production. In Iowa for example, there were approximately 65,000 hog farmers in 1980 but only 10,000 in 2002, and the average number of hogs per farm increased from 200 to 1,400 over the same period of time (Babcock et al., 2003). See the graphs below for a visual illustration of these trends.

As an example of consolidation within the food industry, the number of Iowa pig farms shows a very clear downward trend over the 25 years from 1982 to 2007.

Here, an opposite trend is obvious. While the number of farms has decreased as in the above graph, the production level/size of each of those farms has greatly increased. Together these two trends illustrate very clearly the idea of farm consolidation as described in the above paragraphs: fewer and fewer farms are producing more and more. Both graphs are from this 2012 Food and Water Watch report on food monopolies.

This farm consolidation then leads to a decrease in the percentage of rural population employed in agriculture, and a subsequent decrease in the overall rural population. Though many individual rural counties have experienced out-migration over the past several decades, 2010 marked the first year of net decrease in rural population nationwide (USDA ERS, 2012). As many scholars propose, farm consolidation and the cost-price squeeze caused by the modernization of the food chain play a part in this trend. Along with these broader national and international trends of farm consolidation and decrease in rural population, it is possible to examine the more specific effects of food chain modernization on the smaller scale of a single state.

Another trend beginning in Iowa in the early 1980s helps to illustrate one specific on-the-ground effect of the modernization of the food chain on rural spaces and people. In Iowa, which has long relied economically on pork production, pigs are increasingly raised by contract growers. In these arrangements, contracting firms supply the farmer with young pigs and inputs such as feed, pay the farmer for fattening the pigs, and then market the full-grown pigs. As a result, the farmer has clearly lost autonomy in that he does not own his animals and his production methods are “carefully specified and monitored” (Page, 1996: 390). In these relationships, “nominally independent growers are brought under the control of agro-industrial firms that orchestrate relationships within the commodity chain” (Page, 1996: 390). Along with this loss of autonomy, contract production has harmed the “strong collective identity” of farmers by dividing members of farm organizations who differ in their opinion of contract farming (Page, 1996: 391).

This “agricultural restructuring” caused by contracting firms also occurs at other parts in the food chain, for example companies who produce animal feed, land grant universities, and extension services (Page, 1996: 392). Contracting firms attempt to bring in their own researchers, beginning to take over the role of researchers from universities. Additionally, contracting firms have integrated some feed companies to produce for them, but only companies who are structurally centralized enough to be compatible with the structure of these firms. This harms the business of more localized feed companies. In summary, this trend of contract farming (which is no doubt part of the larger trend of increasing economic influence of the non-production components of a modernizing food chain) stands to harm rural economies and divide rural communities politically.

In the last 50 years or so, alternatives to this conventional modernized food chain have begun to spread. Though on-farm practices between the producers involved in conventional and alternative food chains are highly different, here I focus on the fact that alternative food chains are structurally different, shorter, and more localized than the older conventional ones. They involve fewer economic components and are often stripped down to the simplest of chains which involve only manufacturers of farm inputs, a producer, and a consumer.

Before addressing the effects of new alternative food chains on rural spaces and communities, it is essential to link their development to the modernized food chain and identify their development as a direct reaction to the modernization of the food chain. This vital reactionary element of alternative food chains can be identified in the so-called local food movement, which is framed as the opposite and counter-movement to the globalization of food chains. Consumers’ demand for local food is thus an ideological rejection of the distance between producer and consumer inherent in a global food chain. As the authors of a 2003 study in the Journal of Rural Studies asserted, these shortened alternative food chains seek to “challenge the time space distantiation that characterizes the continuing development of the dominant agrifood system” (Allen et al., 2003: 73).

Additionally, globalized food chain components are often managed by offices that are far away from the region in which the company’s products are sold and therefore the management cannot respond to the specific consumer preferences of a given locality. The “disassociation between these traditional large firms and the local consumer base” has allowed space for more localized food companies and food chains to develop and meet the demands of local consumers (Blay-Palmer and Donald, 2006: 390). This inability of large companies to meet localized consumer demand, in addition to consumers’ increasing ideological resistance to the products of globalized food chains and preference for local foods, together point to the important role consumers have played in the formation of alternative food chains.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly when considering rural communities, the alternative food chain can also be described as a reaction against the conventional food chain on the part of the producer. Farmers who do not abandon their farms in the face of the economic hardship of the conventional food chain may convert to the production and distribution style of the alternative food chain. For example, in their 2000 study, Marsden et al. cite the establishment of the Llyn beef-producers co-operative in Wales in 1997 as an “example of the development of short food supply chains prompted by the severe crisis and cost-price squeeze on the British livestock industry” (Marsden et al., 2000: 435). Likewise, Banks et al. call the value added to farm products by the alternative food chain a “way out of the [cost-price] ‘squeeze’” (Banks et al., 2003: 397).

Farmers may even join the alternative food chain partially on ideological grounds; in the words of Missouri farmer Russ Pisciotta, “This is more like farms used to be. The old farmers fed people directly, rather than going through middle men [sic]” (Pisciotta in McEowen, 2006). Clearly, alternative food chains are a reaction by producers and consumers alike to the modernization and globalization of the conventional food chain. Thus, alternative food movements have often been characterized by their ability to “re-spatialize” food as a response to the conventional food chain, in which the supply of food has been globalized to such an extent that it no longer exists spatially in the minds of consumers (Marsden and Sonnino, 2000: 183).

After placing these food movements in context, it is possible to examine their effects on rural communities and spaces. Firstly, as in the example of Llyn beef cited above, the alternative food chain can provide an economic outlet for struggling farmers to improve their income. More common in the alternative food chain, however, are the producers which begin with alternative production methods and have founded farms in the last 50 years and often much more recently. In either of these cases, the alternative food chain adds value to farmers’ products by emphasizing higher quality and therefore fetching higher prices than products of the conventional food chain. Banks et al. estimate that in Germany, Italy, and France, alternative food chains (for example cooperatives of producers who market directly to the consumer) provide an increase of 7-10% in the net value of a product added by the farmer (Banks et al., 2003: 407).

The alternative food chain can also improve farmers’ incomes and fuel rural economies with tourism. For example, farms such as the Rhöngold organic dairy in Germany offer consumers “high-quality and region-specific products” as well as an image of pristine rural, natural landscape which together attract agritourism and rural tourism (Knickel and Renting, 2000: 515). This tourism contributes significantly to farmers’ incomes. Considering this tourism as well as the added product values discussed earlier, many scholars assert rather generally that alternative food chains can “revitalize rural areas” and have “economic benefits for the region as a whole” (Marsden and Sonnino, 2000: 181, 182).

While I believe this is true, the effects of alternative food chains on rural areas are no doubt more complex than this beginning designation might imply. For example, the emergence of alternative food chains can also result in competition between these chains and conventional ones (Marsden and Sonnino, 2000: 196). Though I surmise that the net benefits or costs of food chain competition are difficult to assess, this competition complicates the generalized economic benefits that alternative food chains bring to rural areas. Though I could not find specific on-the-ground examples of this food chain competition in the current scholarship, one form that results is competition on the retail level between corporate and local retailers (Marsden and Sonnino, 2000: 197). Also inherent in the different structure of alternative food chains is a different relationship between the producer and other components of the food chain. For example, the alternative food chain necessarily includes few or no distributors and therefore affects the business of regional food distributors, but in ways that are very hard to assess (Knickel and Renting, 2000: 516).

Thus, we can begin to see the complexity of the effects of the alternative food chain on rural development. Though it is widely agreed that this food chain is generally a positive force of revitalization and regrowth, it is also importantly a more complex force of “reshaping” and restructuring of rural spaces (Marsden and Sonnino, 2000: 196). The complexity and variability of this reshaping makes it difficult to classify and evaluate, but it may cause competition between conventional and alternative food chains and affect rural food distributors tied to agriculture.

Though I do believe strongly that these effects on the rural community as well as the broader trends of farm consolidation mentioned earlier are results of the modernization of the food chain, it is important to acknowledge the inherent difficulty in drawing direct cause-and-effect relationships in this field. Even though trends of contract farming and farm consolidation are easy to identify, distinct causes are more difficult to discern. For example, many argue that the modernization and mechanization of on-farm practices (more so than the modernization of the structure of the food chain) contributes to the rural out-migration because machines have in many instances taken the place of people previously employed in agriculture.

I have tried in my writing here to focus on the effects of changes in food chain structure rather than the effects of changes in on-farm practices, because I believe the former is an under-studied and under-acknowledged area of research. However, this is clearly not an insignificant subject. The cost-price squeeze caused largely by structural changes in the food chain as well as the development of alternative food chains in response to these difficulties have large and complex effects on rural communities, as well as consumers outside these communities, and the health of the environment. The various social and economic effects of food chain modernization include farm consolidation and subsequent decreases in rural population, as well as the more complex political and social implications of contract farming. The alternative food chain has developed in response to these as well as other downsides to the modernized conventional food chain, and has complex but often positive effects on rural communities. These include increasing farmers’ incomes, causing competition between farmers who follow different production models, and affecting other rural industries tied to agriculture.

The structural changes in the food chain responsible for this larger reshaping of rural communities are no doubt inextricably tied to changes in on-farm practices, but the difficulty in distinguishing between the two does not take away from the importance of the former. It is essential to take all these complexities into consideration when attempting to form a comprehensive view of conventional and alternative food chains and their diverse impacts on rural communities. I strongly believe that this knowledge can benefit consumers and activists currently involved in the local food movement and other alternative food chains, helping these people to truly understand the movement they are reacting to, the movement they are participating in, and the implications of both of these for the farmers growing our food.

A shocking depiction of widespread food industry concentration/consolidation, as shown by the hugely disproportionate market share held by just the top four companies of different products, ranging from 55% to 84%. This image is from a Farm Aid article, though I don’t know what year the data is from.

I didn’t include my list of references because I figured no one really wanted to read a long list of formal citations. If you are interested in reading any of the articles I’ve cited here, just e-mail me (below) and I can send the titles your way, though you likely won’t have access to most unless you can use your university’s database or the like.

Thanks for reading!

Simon

Feel free to contact me with any questions or comments at eatfortheearth@gmail.com and check out my twitter, @Eat4theEarth, for interesting links and articles.